Domain modelling with state machines

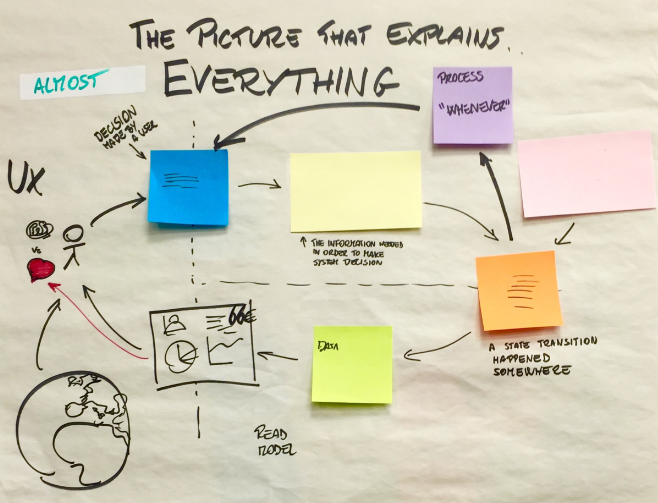

Since I started learning DDD and Event Sourcing in particular, I was always fascinated by the picture that explains everything by Alberto Brandolini.

It describes an high level perspective on how to model domains using the elements of event storming. Briefly, it proposes to structure the flow of an application in the following fashion:

- a user requests to the system the execution of a

command. - an

aggregateprocesses thecommandand according to its own inner state emits a series ofevents. - an

eventmight be processed by apolicy, which in return could send newcommandsto the system. - an

eventmight be processed also by aprojection, which updates aread model. - based on the information presented in the

read model, the user requests a newcommandand the cycle starts again.

What I always liked about this approach to modelling an application is how easily it could be transformed into working software, using event sourcing and cqrs. Still, being at a high level of abstraction, it ignores how to implement aggregates, policies and projections.

In this blog post I would like to discuss how using state machines to implement aggregates, policies and projections lead to the creation of a precise and composable domain model.

State machines

With the term state machine I’ll be referring in particular to Mealy machines, which are finite-state machines whose output values are determined both by their current state and their current input. We’re not going into the technical definition of a Mealy machine, just think of it as a black box with an inner state, which could receive inputs of a predefined type a a can return outputs of type b while modifying the inner state.

Trying to model a Mealy machine in code, we can represent it with the following type:

type Mealy a b = a -> (b, Mealy a b)

This means that a Mealy machine which accepts inputs of type a and outputs values of type b can be represented by a function that receives an a and returns a pair composed by the output b and a new version of the machine. Notice how the inner state is not explicit in this definition.

Mealy machines are extremely nice to implement because you just basically need to say what to do for every possible state and input. We’ll see examples of this further on.

State machines are composable

The other huge benefit of using Mealy machines is that they are composable! There are several ways to take two state machines and create a bigger state machines whose behaviour is completely determined by the smaller ones.

For example, Mealy machines form a category, meaning that whenever we have two Mealy machines of type Mealy a b and Mealy b c we can compose them to obtain a Mealy machine of type Mealy a c. In other terms, we can create a state machine which computes in sequence two smaller state machines.

Moreover, if we have two Mealy machines of type Mealy a b and Mealy c d, we can build a state machine of type Mealy (a, c) (b, d) which processes the two machines in parallel. Also, we could get also a machine of type Mealy (Either a c) (Either b d) which will process only the relevant machine depending on the input.

The are many other ways to combine Mealy machines. If you like Haskell, you can check the Mealy data type instances to find other interesting combinators.

Aggregates are Mealy machines

An aggregate is a key component of the write model, which has the role of ensuring that invariants are preserved. It is often modelled as a stateful component which receives commands and emits events in response. This description fits very well in our model of a state machine, and we can view an aggregate as a Mealy machine which receives commands and emits lists of events

type Aggregate command event = Mealy command [event]

Let’s consider for example a Door aggregate, which could receive the Knock, Open and Close commands and emit the Knocked, Opened and Closed events. We can fully describe its behaviours as a state machine via a function

aggregate :: State -> Command -> ([Event], State)

aggregate IsOpen Knock = ([Knocked], IsOpen )

aggregate IsOpen Open = ([] , IsOpen )

aggregate IsOpen Close = ([Closed] , IsClosed)

aggregate IsClosed Knock = ([Knocked], IsClosed)

aggregate IsClosed Open = ([Opened] , IsOpen )

aggregate IsClosed Close = ([] , IsClosed)

According to the state, which could be either IsOpen or IsClosed, and the incoming command, we return a list of emitted events and the new state of the Door aggregate.

Projections are Mealy machines

A projection is a component of our system that updates a read model according to an incoming stream of events. In other terms, it is a stateful component which receives events and outputs a read model. This fits in our state machine model, too! We can view a projection as a Mealy machine that consumes events and produces read models

type Projection event readModel = Mealy event readModel

In our door example, suppose we want to count how many times a door has been opened. Our read model could be just a counter

type Counter = Int

If we consider the inner state of our state machine to be Counter, we can represent our projection by the following function

projection :: Counter -> Event -> (Counter, Counter)

projection i Opened = (i + 1, i + 1)

projection i Closed = (i , i )

projection i Knocked = (i , i )

which updates the returned counter while keeping updated also the internal projection state.

Policies are Mealy machines

The remaining piece of the puzzle are policies, which allow us to react to events emitted by aggregates and request new commands accordingly. Also policies can be modelled using state machines.

In our example, consider for example the following policy: “Whenever someone knocks on a door, the door should open”. We could model this with something which resembles the following code, where there actually is no state involved (as denoted by the () symbol, meaning that the state has only one possible value)

policy :: () -> Event -> ([Command], ())

policy () Opened = ([] , ())

policy () Closed = ([] , ())

policy () Knocked = ([Open], ())

This is basically dual to what an aggregate does. An aggregate processes commands to output events, while a policy processes events to output commands.

Escaping from purity

In our discussion, up to this point, everything is pure and deterministic. It would be nice if every real system would be so, but this is often not the case. More often than not we need to interact with the outside world and communicate with external services. So we need to find a way to fit non pure operations somewhere inside our model.

Aggregates are the most delicate part of our system, the one which is tasked to check and preserve all the system invariants; therefore we would like to keep them pure to be able to easily inspect and test their behaviour.

Projections are pure operations by nature, they just need to process event streams to create different visualizations of the data contained by the events themselves. Therefore it doesn’t make sense to have projections which are not pure operations.

The only option we are left with are policies. And it makes a lot of sense to have side effects in policies. When aggregates emit events, we project them to read models so that users can react to them with new commands. Policies automate all this process, where it is possible, substituting an external automatic system to the user. Therefore the standard flow of policies become

- receive an event which needs to be processed

- interact with the external world

- according to the response received from the external world, emit a new command

For example, a policy could be used to model a payment system interacting with an external gateway. A policy PaymentPolicy could receive an event PaymentRequested and react to it by asking the remote gateway to process the actual payment. According to the response of the gateway, positive or negative, the policy can emit a CompletePayment or a FailPayment command.

For the ones who care about typing, to allow such behaviour, we need to generalize a bit our Mealy type, so that it allows performing generic side effects. We could define a type

type MealyT m a b = a -> m (b, MealyT m a b)

where m represents the possible effects performed by the state machine.

Composing it all back together

Now we have separate state machine to represent an aggregate, a projection and a policy. How do we connect them so that messages can flow between them? As we mentioned above, we need to use combinators which allow us to create a state machine representing our whole application.

First, we can combine our aggregate and our policy, basically to create our write model. To do that we need a combinator

feedback :: Mealy Command [Event]

-> Mealy Event [Command]

-> Mealy Command [Event]

I’m not going into the technical details of its implementation, but it basically needs to run the aggregate with the input command, pass the returned events to the policy one by one obtaining new commands and finally passing those commands back to aggregate itself so that the cycle could continue.

Composing the write model Mealy Command [Event] and our projection Mealy Event Counter is easier. We just pass one by one the events emitted by the aggregate to the projection.

In this way we obtain a stateful application represented by a state machine with type Mealy Command Counter.

Conclusion

State machines are an easy way to represent stateful computations coming with three big benefits:

- they are composable. This allows us to create complex application combining smaller pieces using a small number of combinators.

- they are easily representable. State machines can be represented graphically, providing a nice visualization of the behaviour of the system. Moreover, you could do also the opposite, trying to generate a scaffolding of your code from a graphical representation (or a serialized representation, as UML statecharts)

- they are easy to implement. The mental model of a state machine is pretty simple, leaving you to consider which output to return given a state and an input.

Components of an architecture based on DDD/ES/CQRS lend themselves to be easily modelled as state machines, defining the wiring which needs to be used to let the messages flow through the application. Moreover, using state machines as our basic abstraction allows us to combine our DDD/ES/CQRS components with other components which could have a different architecture.

I’m confident that such an approach could be used to model basically any system. If, after reading this post, you’re not convinced by this claim, please contact me with your doubts because I’d like to be able to test this approach against more challenging examples.